Restless legs syndrome and related disorders

Highlights

Overview

- Restless leg syndrome (RLS) can be temporary (during pregnancy) or chronic and long-term, due to many medical conditions and genetic risk factors.

- The condition involves the sensation of "pulling, searing, drawing, tingling, bubbling, or crawling" beneath the skin, usually in the calf area, causing an irresistible urge to move the legs. These sensations can sometimes affect the thighs, feet, and even the upper body. RLS-type symptoms may also occur in the arms. Treatment often includes over-the-counter remedies and lifestyle changes, iron supplementation for confirmed iron deficiency, and prescription medications for pain and relief of symptoms.

RLS and PLMD:

- Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) is a condition where leg muscles contract and jerk every 20 - 40 seconds during sleep. Such movements may last less than 1 second, or as long as 10 seconds.

- Unlike RLS, contractions in PLMD usually do not wake patients.

- Eighty percent of RLS sufferers have PLMD, but only about 30% of people with PLMD also have RLS.

Medication Alert:

- In July 2010, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning of serious, potentially life-threatening side effects resulting from the use of quinine (Qualaquin) for nighttime leg cramps. These side effects include dangerously low blood platelet counts (platelets help the blood clot) and permanent kidney damage.

New Treatment:

- An antiseizure agent, gabapentin enacarbil (Horizant), has been approved by the FDA for moderate-to-severe RLS. Common side effects included mild sleepiness and dizziness.

Introduction

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is an unsettling and poorly understood movement disorder affecting 3 - 15% of the general population. RLS can affect both children and adults. Although effective treatments are available, the condition often remains undiagnosed.

Symptoms of RLS. The core symptom of RLS is an irresistible urge to move the legs (medically known as akathisia). Some people describe this symptom as a sense of unease and weariness in the lower leg, which is aggravated by rest and relieved by movement. Specific characteristics of RLS include:

- "Pulling, searing, drawing, tingling, bubbling, or crawling" beneath the skin, usually in the calf area, causing an irresistible urge to move the legs. These sensations can occur mostly in the lower legs, but they can sometimes affect the thighs, feet, and even the upper body. RLS-type symptoms may also occur in the arms. These may be the first symptoms of RLS in some people.

- About 80% of patients with RLS also have semi-rhythmic movements during sleep, a condition called periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD). (See description below)

- Itching and pain, particularly aching pain, may be present.

- Patients experience symptoms when they feel most relaxed and their legs are at rest. (Movement, however, brings relief.) Symptoms usually occur at night when lying down, or sometimes during the day while sitting.

- Episodes of RLS usually develop between 10 p.m. and 4 a.m. Symptoms are often most severe shortly after midnight. They usually disappear by morning. If the condition becomes more severe, people may begin to have symptoms during the day. These symptoms are always worse at night, however.

- At night, the unpleasant sensations and the resulting uncontrollable urge to move the legs can often disturb sleep. Ignoring the need to move the legs usually only builds up tension until they jerk uncontrollably. If patients experience symptoms during the day, they usually feel compelled to move their legs in order to relieve the symptoms, making it difficult to sit during air or car travel, or through classes or meetings.

Late-onset and Early-onset Forms. There appear to be two forms of RLS, early-onset and late-onset. Each form may have different characteristics:

- People with early-onset RLS (occurring in the teenage years or earlier) tend to have a family history of the disorder. They also usually have RLS without accompanying pain.

- People with late-onset RLS usually do not have a family history of RLS. Their condition is more likely the result of a problem with the nervous system, and symptoms may include pain in the lower legs.

Periodic Limb Movement Disorder

Another medical term for periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) is nocturnal myoclonus. PLMD symptoms include:

- Episodes that usually occur during the night, peaking near midnight, as they do in restless legs syndrome.

- Leg muscles contract and jerk every 20 - 40 seconds during sleep. Such movements may last less than 1 second, or as long as 10 seconds.

- Unlike RLS, contractions in PLMD usually do not wake patients. PLMD is distinct from the brief and sudden movements that occur just as people are falling asleep, jolting them awake.

Although 80% of RLS sufferers have PLMD, only about 30% of people with PLMD also have RLS. While treatments for the two conditions are similar, PLMD is a separate syndrome. PLMD is also very common in narcolepsy, a sleep disorder that causes people to fall asleep suddenly and uncontrollably.

Causes

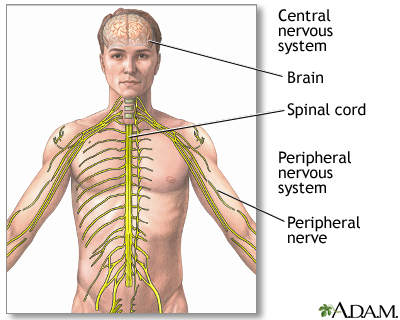

The main cause of RLS is unknown. Researchers are investigating neurologic (nervous system) problems that may arise either in the spinal cord or the brain. One current theory suggests that a deficiency in a brain chemical called dopamine causes restless legs syndrome.

RLS may often have a genetic basis, particularly in those who develop it before age 40. When the condition occurs in older adults, it is most likely due to a neurological problem.

Genetic Factors

People with RLS often have a family history of the disorder. Researchers have detected at least six genetic locations or factors that might be responsible for this condition. Two of the genes are associated with spinal cord development. None of the genes have been associated with dopamine or iron-regulating systems, though these are considered likely causes of the condition.

Neurological Abnormalities

Dopamine and Neurologic Abnormalities in the Brain. A variety of studies support the theory that an imbalance in neurotransmitters (chemical messengers in the brain), notably dopamine, may play a part in RLS. Dopamine triggers numerous nerve impulses that affect muscle movement. The effect is similar to what happens in Parkinson's disease. Moreover, drugs that increase dopamine levels treat both disorders. However, Parkinson's disease itself does not seem to increase the risk for RLS. Nor does RLS early in life predispose a person to Parkinson's later on.

Neurologic Abnormalities in the Spine. Other research suggests that restless legs syndrome may be due to nerve impairment in the spinal cord. Researchers thought that such abnormalities were likely to start in nerve pathways in the lower spine. However, some patients with RLS have symptoms in the arms, indicating that the upper spine may also be involved.

Neuropathy. Some experts suggest that RLS, particularly if it occurs in older adults, may be a form of neuropathy, which is an abnormality in the nervous system outside the spine and brain. So far, there is no evidence of a cause and effect relationship between neuropathy and RLS.

Abnormalities of Iron Metabolism

Iron deficiency, even at a level too mild to cause anemia, has been linked to RLS in some people. Studies suggest, in fact, that RLS in some people may be due to a problem with getting iron into cells that regulate dopamine in the brain. Some studies have reported RLS in 25 - 30% of people with low iron levels.

Deficiencies in Cortisol

Some research suggests that low cortisol levels in the evening and early night hours may be related to restless leg symptoms. Some patients experienced improvement in symptoms with low-dose hydrocortisone injections.

Causes of Periodic Limb Movement DisorderThe cause or causes of PLMD are not clear. Some research suggests that it may be due to abnormalities in the autonomic nervous system, which regulates the involuntary actions of the smooth muscles, heart, and glands.

Risk Factors

RLS may affect 3 - 15% of the general population. It is more common in women than in men, and its frequency increases with age. The disorder affects an estimated 10 - 28% of adults older than age 65. In about 40% of patients, RLS begins in adolescence.

An international study showed that 2% of children ages 8 - 17 have RLS symptoms. RLS may be more common than epilepsy and diabetes in children and teens.

Family History

As many as two-thirds of people with restless legs syndrome (RLS) have a family history of the disorder. In people with a family history of the condition, RLS is more likely to occur before they turn 40. (A family history of RLS is less likely in people who develop it as older adults.) RLS is also more common in people from northern and western Europe, giving added support for a genetic basis for some cases.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

RLS and PLMD in children are strongly associated with inattention and hyperactivity. Up to a quarter of children diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may also have RLS, sleep apnea, and PLMD, and this may actually contribute to inattentiveness and hyperactivity. The disorders have much in common, including poor sleep habits, twitching, and the need to get up suddenly and walk about frequently. Some evidence suggests that the link between the diseases may be a deficiency in the brain chemical dopamine.

Pregnancy

About 20% of pregnant women report having RLS. The condition usually goes away about a month after delivery. RLS in this population has been strongly associated with deficiencies in iron and the B vitamin folate.

Dialysis

Between 20 - 62% of people undergoing dialysis report restless legs syndrome. Symptoms often disappear after a kidney transplant.

Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety can cause restlessness and agitation at night. These symptoms can cause (or strongly resemble) restless legs syndrome.

Other Conditions Associated with Restless Legs Syndrome

The following medical conditions are also associated with restless legs syndrome, although the relationships are not clear. In some cases, these conditions may contribute to RLS, or they may have a common cause. In some cases, they may coexist due to other risk factors:

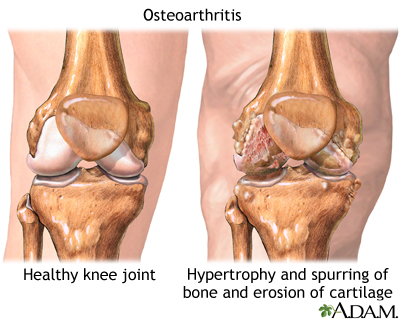

- Osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease). About 72% of patients with RLS also have osteoarthritis, a common type of arthritis affecting mostly older adults.

- Varicose veins. Varicose veins occur in 14% of patients with RLS.

- Obesity

- Diabetes -- people with type 2 diabetes may have higher rates of secondary RLS. Nerve pain (neuropathy) related to their diabetes cannot fully explain this increased rate in RLS.

- Hypertension

- Hypothyroidism (a condition in which the thyroid gland does not make enough hormones)

- Fibromyalgia (chronic pain of unknown cause)

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Emphysema (a lung disease usually caused by smoking)

- Chronic alcoholism

- Sleep apnea (pauses in breathing during sleep) and snoring

- Chronic headaches

- Brain or spinal injuries

- Many muscle and nerve disorders; hereditary ataxia, a group of genetic diseases that affects the central nervous system and causes loss of motor control, is of particular interest. Researchers believe that hereditary ataxia may supply clues to the genetic causes of RLS.

Environmental and Dietary Factors

Several environmental and dietary factors can worsen or provoke restless legs syndrome:

- Iron deficiencies. People who are deficient in iron are at risk for restless legs syndrome, even if they do not have anemia

- Folic acid or magnesium deficiencies

- Smoking

- Alcohol abuse

- Caffeine (coffee drinking is specifically associated with PLMD)

- Stress

- Fatigue

- Prolonged exposure to cold

Medications

Drugs that worsen or provoke RLS include:

- Antidepressants

- Antipsychotic drugs

- Anti-nausea drugs

- Calcium channel blockers (mostly used to treat high blood pressure)

- Metoclopramide (used to treat various digestive diseases)

- Antihistamines

- Oral decongestants

- Diuretics

- Asthma drugs

- Spinal anesthesia (anesthesia-induced restless legs syndrome typically disappears on its own within several months)

Risk Factors for Periodic Limb Movement Disorder

About 6% of the general population has PLMD. Among the elderly, the prevalence increases to 25 - 58%. Studies suggest that PLMD may be especially common in elderly women. As with RLS, numerous conditions are associated with PLMD. They include sleep apnea, spinal cord injuries, stroke, narcolepsy, and diseases that destroy nerves or the brain over time. Certain medications, including some antidepressants and anti-seizure medications, may also contribute to PLMD.

Complications

RLS rarely results in any serious consequences. However, in some cases severe and recurrent symptoms can cause considerable mental distress, sleep deprivation, and daytime sleepiness. In addition, RLS is worse when resting; people with severe RLS may avoid daily activities that involve long periods of sitting, such as going to movies or traveling long distances.

Sleep Deprivation

Sleep deprivation, and the daytime sleepiness that follows, is increasingly recognized as a cause of mood disruption and a contributor to industrial errors and motor vehicle crashes.

Effect on Daily Performance and Activities. Studies suggest that sleeplessness worsens many waking behaviors. These include:

- Concentration. Deep sleep deprivation appears to impair the brain's ability to process information.

- Task performance. Missing several hours of nightly sleep over the course of a week can negatively affect performance levels and mood. In fact, sleep deprivation can cause impaired performance levels comparable to those of intoxicated people.

- Learning. Whether sleeplessness significantly impairs learning is unclear. Some studies have reported problems in memorization, although others have found no differences in test scores between people with temporary sleep loss and those with regular sleep cycles.

Psychiatric Effects

People with restless legs syndrome are more apt to be socially isolated, to have frequent daytime headaches or depression, and to complain of reduced libido or other problems related to insufficient sleep.

RLS can contribute to insomnia. Insomnia itself can increase the activity of hormones and pathways in the brain that produce emotional problems. Even modest alterations in waking and sleeping patterns can have significant effects on a person's mood. Persistent insomnia may even predict the future development of mood disorders in some cases.

It is not clear if RLS is responsible for negative mood states or if anxiety or depression contributes to RLS. Anxiety can cause agitation and leg restlessness that resemble RLS, and depression and RLS symptoms also overlap. In addition, certain types of antidepressant drugs -- such as serotonin reuptake inhibitors -- can increase periodic limb movements during sleep.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of restless legs syndrome often relies mainly on the patient's description of symptoms. In general, the recommended approach is first to take a sleep and personal history. The doctor may conduct an interview that includes the following questions:

- How would you describe your sleep problem?

- How long have you had this sleep problem?

- How long does it take you to fall asleep?

- How many times a week does the problem occur?

- How restful is your sleep?

- What do your leg problems feel like (such as cramps, twitching, and crawling feelings)?

- What is your sleep environment like? Noisy? Not dark enough?

- What medications are you taking (including the use of antidepressants and self-medications -- such as herbs, alcohol, and over-the-counter or prescription drugs)?

- Are you taking or withdrawing from stimulants, such as coffee or tobacco?

- How much alcohol do you drink per day?

- What stresses or emotional factors may be present in your life?

- Have you experienced any significant life changes?

- Do you snore or gasp during sleep? (This may be an indication of sleep apnea. Sleep apnea is a condition in which breathing stops for short periods many times during the night. It may worsen symptoms of restless legs syndrome or insomnia.)

- If you have a bed partner, does he or she notice that you have jerking legs, interrupted breathing, or thrashing while you sleep?

- Are you a shift worker?

- Do you have a family history of RLS or periodic movement limb disorder, "growing pains" at night, or night walking?

Keeping a Record of Sleep. To help answer these questions, the patient may need to keep a sleep diary. Every day for 2 weeks, the patient should record all sleep-related information, including responses to questions listed above described on a daily basis. Recording sleep behavior using an extended-play audio or videotape can be very helpful in diagnosing sleep apnea.

A bed partner can help by adding their observations of the patient's sleep behavior.

Sleep Disorders Centers

Some high-risk patients may need to consult a sleep specialist or go to a sleep disorders center before their sleep problem can be diagnosed. At most centers, patients undergo an in-depth analysis, usually supervised by a team of consultants from various specialties, who can provide both physical and psychiatric evaluations. Centers should be accredited by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine.

Among the signs that may indicate a need for a sleep disorders center are:

- Insomnia due to psychological disorders

- Sleeping problems due to substance abuse

- Snoring and sudden awakening with gasping for breath (possible sleep apnea)

- Severe restless legs syndrome

- Persistent daytime sleepiness

- Sudden episodes of falling asleep during the day (possible narcolepsy)

Polysomnography

Overnight polysomnography involves several tests to measure different functions during sleep. It is typically performed in a sleep center and may help rule out sleep apnea or confirm the effectiveness of RLS treatments.

The patient arrives about 2 hours before bedtime without having made any changes in daily habits. Polysomnography electronically monitors the patient as he or she passes, or fails to pass, through the various sleep stages. Polysomnography tracks the following:

- Brain waves

- Body movements

- Breathing

- Heart rate

- Eye movements

- Changes in breathing and blood levels of oxygen

Actigraphy

Actigraphy uses a small wristwatch-like device (such as Actiwatch) to monitor sleep quality in people with suspected RLS, PLMD, insomnia, sleep apnea, and other sleep-related conditions. Patients can wear the device on their wrists or ankles. It measures and records muscle movements during sleep. For example, with PLMD, actigraphy can provide information on the total duration of movements, the number of occurrences, whether PLMD occurs simultaneously in both legs, and its effects on sleep.

Actigraphy is not as accurate as polysomnography because it cannot measure all the biological effects of sleep. It is more accurate than a sleep log, however, and very helpful for recording long periods of sleep.

Sleepiness Scale

The Epworth sleepiness scale uses a simple questionnaire to measure excessive sleepiness during eight situations.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale | |

Situation | Chance of Dosing |

Sitting and reading | (Indicate a score of 0 to 3) 0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing |

Watching TV | (Indicate a score of 0 to 3) 0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing |

Sitting inactive in a public place | (Indicate a score of 0 to 3) 0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing |

Riding as a passenger in a car for an hour without a break | (Indicate a score of 0 to 3) 0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing |

Lying down to rest in the afternoon when circumstances permit | (Indicate a score of 0 to 3) 0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing |

Sitting and talking to someone | (Indicate a score of 0 to 3) 0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing |

Sitting quietly after a lunch without alcohol | (Indicate a score of 0 to 3) 0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing |

Sitting in a car while stopped for a few minutes in traffic | (Indicate a score of 0 to 3) 0 = no chance of dozing 1 = slight chance of dozing 2 = moderate chance of dozing 3 = high chance of dozing |

Score Results 1 - 6: Getting enough sleep. 4 - 8: Tends to be sleepy but is average. 9 and over: Very sleepy and suggestive of sleep-disordered breathing. Patient should seek medical advice. | |

Diagnosing Iron Deficiency Anemia and Its Causes

Because of the high association between restless legs syndrome and iron deficiency, a test for low iron stores should be part of the diagnostic workup in RLS. There are two steps in making this diagnosis:

- The first step is to determine if a person is actually deficient in iron.

- If iron stores are low, the second step is to diagnose the cause of the iron deficiency, which will help determine treatment.

Determining if Iron Stores are Low: The following findings are important in determining that a person is iron deficient:

- Blood cells viewed under the microscope are pale (hypochromic) and abnormally small (microcytic). These findings suggest iron deficiency, but they can appear in both anemia resulting from chronic disease and thalassemia (an inherited blood disorder).

- Hemoglobin and iron levels are low. These findings further suggest iron deficiency, but they can also occur in cases of anemia due to chronic disease.

- Ferritin levels are low. Ferritin is a protein that binds to iron; low levels typically mean patients do not have enough iron in their bodies. However, normal levels of ferritin in the blood do not always mean a patient has enough iron. For example, pregnant women in their third trimester or patients with a chronic disease may not have enough iron even with normal or high ferritin levels.

- A test that measures a factor called serum transferrin receptor (TfR) is proving to be very sensitive in identifying iron deficiency in some patients, including the elderly with chronic diseases and possibly pregnant women.

When iron deficiency anemia is diagnosed, the next step is to determine what causes the iron deficiency itself. Menstrual blood loss is a common cause of iron deficiency. Tests to check for an underlying cause of iron deficiency, such as gastrointestinal (digestive tract) bleeding, are particularly important in men, postmenopausal women, and children. [See In-Depth Report #57: Anemia.]

Other Laboratory Tests

Certain laboratory tests may be helpful in determining causes of restless legs syndrome (RLS) or conditions that rule it out. They include:

- Blood glucose tests for diabetes

- Tests for kidney problems

- In certain cases, tests for thyroid hormone, magnesium, and folate levels

- Electromyography (recording the electrical activity of muscles) for neuropathy, radiculopathy (problem with the nerve roots), myelopathy (problem with the spinal cord)

- Central nervous system MRI for myelopathy or stroke

Ruling Out Other Leg Disorders

In addition to other sleep-related leg disorders, many other medical conditions may have features that resemble restless legs syndrome (RLS). The doctor will need to consider these disorders in making a diagnosis.

Peripheral Neuropathies. Peripheral neuropathies are nerve disorders in the hands or feet. Several conditions can cause these disorders, and they can produce pain, burning, tingling, or shooting sensations in the arms and legs. Diabetes is a very common cause of painful peripheral neuropathies. Other causes include alcoholism, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, amyloidosis, HIV infection, kidney failure, and certain vitamin deficiencies. Symptoms of peripheral neuropathies may mimic RLS. However, unlike RLS, they are not usually associated with restlessness, movement does not relieve the discomfort, and they do not worsen at bedtime.

Akathisia. Akathisia is a state of restlessness or agitation, and feelings of muscle quivering. A condition called hypotensive akathisia is caused by failure in the autonomic nervous system. Unlike RLS, it occurs at any time of the day and usually only when the patient is sitting -- not lying down. Drugs used to treat schizophrenia and other psychoses can cause akathisia, as can anti-nausea drugs. The condition also occurs when drugs to treat Parkinson's disease are withdrawn.

Painful Legs and Moving Toes Syndrome. A rare disorder affecting one or both legs, painful legs and moving toes syndrome is marked by a constant, deep, throbbing ache in the limbs and involuntary toe movements. The discomfort may be mild or severe. It gets worse with activity and usually stops during sleep. Usually, the cause is unknown, though it may arise from spinal injuries or herpes zoster infection. The condition is difficult to treat, although the drug baclofen, combined with either clonazepam or carbamazepine, has shown some success. Other treatments that may help include orthotics for the shoes and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

Meralgia Paresthetica. An uncommon nerve condition, meralgia paresthetica causes numbness, pain, tingling, or burning on the front and side of the thigh. It usually occurs on one side of the body, and the cause may be compression of the thigh nerve as it passes through the pelvis. It typically occurs in people aged 30 - 60 years, but it can affect people of all ages. It often goes away on its own.

Nocturnal Leg Cramps

Cramps that awaken people during sleep are very common, and they are not part of restless legs syndrome or periodic limb movement disorder. They can be very painful and may cause a person jump out of bed in the middle of the night. They typically affect a specific area of the calf or the sole of the foot.

What Are Nocturnal Leg Cramps?

Benign nocturnal leg cramps, sometimes known as a charley horse, are muscle spasms in the calf that can occur one or many times during the night. Cramping may also occur in the soles of the feet. They typically last from a few seconds to a few minutes. Some people experience them regularly, others only on isolated occurrences.

Causes of Nocturnal Leg Cramps. In most cases, the cause of nocturnal leg cramps remains unknown. Among the conditions that might cause leg cramps are:

- Calcium and phosphorus imbalances, particularly during pregnancy

- Low potassium or sodium levels

- Overexertion, standing on hard surfaces for long periods, or prolonged sitting (especially with the legs contorted)

- Having structural disorders in the legs or feet (such as flat feet)

- Medical causes of muscle cramping include hypothyroidism, Addison's disease, uremia, hypoglycemia, anemia, and certain medications. Various diseases that affect nerves and muscles, such as Parkinson's, cause leg cramps. Peripheral neuropathy, a complication of diabetes, can cause cramp-like pain, numbness, or tingling in the legs. Patients with kidney disease undergoing dialysis are also prone to leg cramps.

Individuals at Higher Risk for Nocturnal Leg Cramps. Nocturnal leg cramps occur at all ages but peak at different times. They are particularly common in adolescence, during pregnancy, and in older age, affecting up to 70% of adults over age 50 at some point.

Pregnant women and those taking diuretics are also at risk for leg cramps because of low calcium levels and an imbalance in calcium and phosphorus.

Consequences of Nocturnal Leg Cramps. Nocturnal leg cramps, like restless legs syndrome, rarely have any serious consequences. However, they can be extremely painful and long lasting. In some cases, severe and persistent symptoms can cause chronic insomnia and considerable mental distress.

Managing Nocturnal Leg Cramps

Once a cramp begins, straighten the leg, flex the foot upward toward the knee, or grab the toes and pull them toward the knee.

Walking or shaking the affected leg, then elevating it, may also help.

If soreness persists, a warm bath or shower or an ice pack may bring relief.

Lifestyle Tips for Preventing Nocturnal Leg Cramps. Nighttime leg cramps are generally treated with lifestyle changes.

- Everyone with leg cramps should drink plenty of water (at least 6 - 8 glasses daily) to maintain adequate fluid levels.

- To prevent cramps from occurring, nightly stretching exercises may be the best preventive measure (these are generally recommended for RLS, as well). Patients should stand about 30 inches from a wall and, keeping the heels flat on the floor, lean forward and slowly move the hands up the wall to achieve a comfortable stretch. A few minutes on a stationary bicycle at bedtime may also help.

- While in bed, loose covers should be used to prevent the toes and feet from pointing, which causes calf muscles to contract and cramp. Propping the feet up higher than the torso may also help.

- During the week, swimming and water exercises are a good way to keep muscles stretched, and wearing supportive footwear is also important.

Quinine. Quinine had been widely used to prevent leg cramping. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) banned its sale over the counter because it reportedly caused some serious, although rare, side effects. These side effects include bleeding problems and heart irregularities. Other, less serious side effects include headaches, vision problems, and rashes.

The FDA has since banned the marketing of most quinine drugs, cautioning against the off-label (non-approved) use of the drug to treat nocturnal (nighttime) leg cramps. Only one form of the drug, Qualaquin, is approved for sale, for the treatment of some types of malaria. Pregnant women and those with liver problems should avoid quinine in any form. In July 2010 the FDA issued a warning of serious, potentially life-threatening side effects resulting from the use of Qualaquin for nocturnal leg cramps. These side effects include dangerously low blood platelet counts (platelets help the blood clot) and permanent kidney damage.

Supplements. Some small studies indicate that the mineral magnesium, taken as magnesium citrate or magnesium lactate, may provide some benefit to people with leg cramps, including pregnant women.

In one small study, taking vitamin B complex was helpful. Other supplements tried for leg cramps include vitamin E, calcium, and potassium or sodium chloride, but these do not appear to be very effective. Sodium chloride (salt) may be helpful, but Western diets already contain too much sodium.

Treatment

The first step in treating a patient who complains of sleeplessness and restless legs syndrome is to try to improve sleep and eliminate possible causes of RLS. Doctors normally try to achieve these goals without the use of drugs, initially. A non-drug approach is a particularly important first step for elderly patients.

- The doctor should first try to treat any underlying medical conditions that may be causing restless legs.

- If medications may be causing RLS, the doctor should try to prescribe alternatives, if possible.

If the cause cannot be determined, it is best to first try better sleep habits and relaxation methods. These approaches may help, even if the patient needs medications later on.

Lifestyle Changes

Some people report help or relief from restless legs syndrome with the following behaviors or devices:

- Taking hot baths or using cold compresses.

- Stopping smoking.

- Getting enough exercise during the day.

- Doing calf stretching exercises at bedtime.

- Using Ergonomic measures -- for example, patients might find it useful to work at a high stool, where they can dangle their legs. In meetings or during air travel, it is helpful to have an aisle seat.

- Changing sleep patterns -- some patients report that symptoms do not occur if they sleep late in the morning. Therefore, if feasible, patients can try changing sleep patterns.

- Avoiding caffeine, alcohol, and nicotine also improves some cases of RLS.

Some patients recommend alternative treatments for RLS, such as acupuncture and massage. To date, however, there is not enough data on the effectiveness of these treatments.

Dietary Iron

Because restless legs syndrome is associated with iron insufficiency, people with the condition should get enough iron from their diet. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #57: Anemia.] Iron is found in foods either in the form of heme or non-heme iron:

- Foods containing heme iron are the best for increasing or maintaining healthy iron levels. Such foods include (in decreasing order of iron-richness) clams, oysters, organ meats, beef, pork, poultry, and fish.

- Non-heme iron is less well absorbed. About 60% of the iron in meat is non-heme (although meat itself helps absorb non-heme iron). Eggs, dairy products, and iron-containing vegetables (including dried beans and peas) have only the non-heme form. Other sources of non-heme iron include iron-fortified cereals, bread, and pasta products, dark green leafy vegetables (such as chard, spinach, mustard greens, and kale), dried fruits, nuts, and seeds.

Iron Supplements

Iron supplements can significantly reduce symptoms in people with restless legs syndrome who are also iron deficient. Patients should use them only when dietary measures have failed. Iron supplements do not appear to be useful for RLS patients with normal or above normal iron levels.

Supplement Forms. To replace iron, the preferred forms of iron tablets are ferrous salts, usually ferrous sulfate (Feosol, Fer-In-Sol, Mol-Iron). Other forms include ferrous fumarate (Femiron, FerroSequels, Feostat, Fumerin, Hemocyte, Ircon), ferrous gluconate (Fergon, Ferralet, Simron), polysaccharide-iron complex (Niferex, Nu-Iron), and carbonyl iron (Elemental Iron, Feosol Caplet, Ferra-Cap). Specific brands and forms may have certain advantages.

Regimen. A reasonable approach for patients with RLS is to take 65 mg of iron (or 325 mg of ferrous sulfate) along with 100 mg of vitamin C on an empty stomach, 3 times a day.

IMPORTANT: As few as 3 adult iron tablets can poison, and even kill, children. This includes any form of iron pill. No one, not even adults, should take a double dose of iron if they miss one dose.

Tips for taking iron are:

- For best absorption, take iron between meals. (Iron may cause stomach and intestinal disturbances, however. Some experts believe that you can take low doses of ferrous sulfate with food and avoid the side effects.)

- Always drink a full 8 ounces of fluid with an iron pill.

- Keep tablets in a cool place. Bathroom medicine cabinets may be too warm and humid, which may cause the pills to disintegrate.

Side Effects. Common side effects of iron supplements include the following:

- Constipation and diarrhea -- these are rarely severe, although iron tablets can aggravate existing digestive problems such as ulcers and ulcerative colitis.

- Nausea and vomiting may occur with high doses, but you can control this by taking smaller amounts. Switching to ferrous gluconate may help some people with severe digestive problems.

- Black stools are normal when taking iron tablets. In fact, if they do not turn black, the tablets may not be working effectively. This tends to be a more common problem with coated or long-acting iron tablets.

- If the stools are tarry and looking black, if they have red streaks, or if cramps, sharp pains, or soreness in the stomach occurs, bleeding in the digestive tract may be causing the iron deficiency, and the patient should call the doctor immediately.

- Acute iron poisoning is rare in adults, but can be fatal in children who take adult-strength tablets.

Interactions With Other Drugs. Certain medications, including antacids, can reduce iron absorption.

Iron tablets may also reduce the effectiveness of other drugs, including:

- Antibiotics: tetracycline, penicillamine, and ciprofloxacin

- Anti-Parkinson's disease drugs: methyldopa, levodopa, and carbidopa

At least 2 hours should elapse between doses of these drugs and doses of iron supplements.

[For additional information about iron supplements see In-Depth Report #57: Anemia.]

Exercise

Exercise earlier in the day may be one of the best ways to achieve healthy sleep. Vigorous exercise and stimulation within 1 - 2 hours of bed time may worsen restless legs syndrome (RLS). A study found that people who walked briskly for 30 minutes, four times a week, improved minor sleep disturbances after 4 months. Regular, moderate exercise, healthful in any case, may help prevent RLS. Patients report that either bursts of excessive energy or long sedentary periods worsen symptoms.

Pneumatic Compression Device

Pneumatic compression devices wrap an inflatable cuff around the legs. This cuff is attached to a device which then increases pressure around the legs. It is worn for at least an hour, generally around the time symptoms usually begin. Smaller studies have shown it improve symptoms of RLS in some patients.

Medications

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends medications for RLS or PLMD only for persons who fit strict diagnostic criteria, and who experience excessive daytime sleepiness as a result of these conditions. (Excessive daytime sleepiness results from nighttime sleeplessness due to RLS or PLMD symptoms).

More research and physician training is needed to better diagnose and treat RLS with medications in children and adolescents. Little is known about the best way to treat RLS in general, but some experts suggest the following for adults:

- If lifestyle changes do not control the problem, over-the-counter pain relievers should be the first form of treatment.

- People with RLS should have a test for iron deficiency. If they are iron deficient, they should start treatment with iron supplements.

- Dopaminergic drugs (drugs that increase levels of dopamine) are the standard medicines for treating severe RLS, PLMD, or both.

- Other drugs may be helpful if dopaminergic drugs fail, or for patients who have frequent -- but not nightly -- symptoms. These include opiates (pain relievers), benzodiazepines (sedative hypnotic drugs), or anticonvulsants. However, benzodiazepines and opiates can become habit forming and addictive.

Tylenol and Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Before taking stronger medications, people should try over-the-counter pain relievers, such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which include ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, Rufen), naproxen (Anaprox, Naprosyn, Aleve), and ketoprofen (Orudis KT, Aktron).

Although NSAIDs work well, long-term use can cause stomach problems, such as ulcers, bleeding, and possible heart problems. In April 2005, the Food and Drug Administration asked drug manufacturers of NSAIDs to include a warning label on their product that alerts users of an increased risk for heart-related problems and digestive tract bleeding.

Levodopa and Other Dopaminergic Drugs

Dopaminergic drugs increase the availability of the chemical messenger dopamine in the brain, and are the first-line treatment for severe RLS and PLMD. These drugs significantly reduce the number of limb movements per hour, and improve the subjective quality of sleep. Patients with either condition who take these drugs have experienced up to 100% reduction in symptoms.

Dopaminergic drugs, however, can have severe side effects (they are ordinarily used for Parkinson's disease). They do not appear to be as helpful for RLS related to dialysis as they do for RLS from other causes.

Dopaminergic drugs include dopamine precursors and dopamine receptor agonists.

Dopamine Receptor Agonists. Dopamine receptor agonists (also called dopamine agonists) mimic the effects of dopamine by acting on dopamine receptors in the brain. They are now generally preferred to L-dopa (see below). Because they have fewer side effects than L-dopa, including rebound effect and augmentation, these drugs may be used on a daily basis. About 30% of patients who take dopamine receptor agonists have reported augmentations symptoms. As the newer drugs are taken for longer periods and at higher doses, however, their augmentation rates may become closer to those of L-dopa.

Dopamine agonists have been shown to relieve symptoms in 70 - 90% of patients. Dopamine agonists can be ergot-derived (such as cabergoline) or non-ergot derived (such as pramipexole and ropinirole). The newer non-ergotamine derivatives may induce fewer side effects than ergot-derived drugs:

- Ropinirole (Requip) was the first drug approved specifically for treatment of moderate-to-severe RLS (more than 15 RLS episodes a month). Side effects are generally mild but may include nausea, vomiting, drowsiness, and dizziness.

- Pramipexole (Mirapex) is also approved for RLS. However, patients may fall asleep, without warning, while taking this drug, even while performing activities such as driving.

Rotigotine is a patch preparation. Common side effects include back or joint pain, dizziness, decreased appetite, dry mouth, fatigue, sweating, trouble sleeping or upset stomach.

Other Dopamine Agonists. Other dopamine agonists that have shown some promise in small studies include alpha-dihydroergocryptine, or DHEC (Almirid), and piribedil (Trivastal).

Dopamine Precursors. The dopamine precursor levodopa (L-dopa) was once a popular drug for severe RLS. Although it can still be useful, most doctors now prefer the newer dopamine agonists (see above). The standard preparations (Sinemet, Atamet) combine levodopa with carbidopa, which improves the action of levodopa and reduces some of its side effects, particularly nausea. Levodopa can also be combined with benserazide (Madopar) with similar results, but Sinemet is almost always used in America. (Levodopa combinations are well tolerated and safe.)

Patients typically start with a very low dose taken 1 hour before bedtime. The dosage is increased until the patient finds relief. Patients sometimes need to take an extended-release form or to take it again during the night.

Levodopa acts fast, and the treatment is usually effective within the first few days of therapy.

Serious common side effects of L-dopa treatment (and, to lesser extent, of dopamine receptor agonists) are augmentation and rebound. Many studies report that augmentation (worsening of symptoms that occur earlier in the day) occurs in up to 70% of patients who take L-dopa. The risk is highest for patients who take daily doses, especially doses at high levels (greater than 200 mg/day). For this reason, patients should use L-dopa only intermittently (fewer than 3 times per week). The drug should be immediately discontinued if augmentation does occur. Following withdrawal from L-dopa, patients can switch to a dopamine receptor agonist.

The rebound effect causes increased leg movements at night or in the morning as the dose wears off, or as tolerance to the drug builds up.

Regimens. The effects of L-dopa are apparent in 15 - 30 minutes. Dopamine receptor agonists, meanwhile, take at least 2 hours to start working. Some doctors recommend regular use of dopamine receptor agonists for patients who experience nightly symptoms, and L-dopa for those whose symptoms occur only occasionally.

Side Effects. Common side effects of dopaminergic drugs vary but may include feeling faint or dizzy (especially when standing up), headaches, abnormal muscle movements, rapid heartbeat, insomnia, bloating, chest pain, and dry mouth. Nausea may be especially common. Adding the drug domperidone may help to relieve this side effect. In rare cases, dopaminergic drugs can cause hallucinations or lung disease.

Because these drugs may cause daytime drowsiness, patients should be extremely careful while driving or performing tasks that require concentration.

Long-term use of dopaminergic drugs can lead tolerance, which results in to loss of effectiveness. Adding a drug called entacapone (Comtan) may prolong the duration of action of carbidopa-levodopa therapy, but it can cause nausea.

Rebound effect, augmentation, and tolerance can reduce the value of dopaminergic drugs in the treatment of RLS. Using the lowest dose possible can minimize these effects.

Withdrawal Symptoms. Patients who withdraw from these drugs typically experience severe RLS symptoms for the first 2 days after stopping. RLS eventually returns to pre-treatment levels after about a week. The longer a patient uses these drugs, the worse their withdrawal symptoms.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam (Klonopin), are known as sedative hypnotics. Doctors prescribe them for insomnia and anxiety. They may be helpful for some patients with restless legs syndrome (RLS) that disrupts sleep. Clonazepam may be particularly helpful for children with both periodic limb movement disorder and symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The medicine also may be helpful for patients with RLS who are undergoing dialysis.

Side Effects. Elderly people are more susceptible to side effects. They should usually start at half the dose prescribed for younger people, and should not take long-acting forms. Side effects may differ depending on whether the benzodiazepine is long-acting or short-acting.

- The drugs may increase depression, a common condition in many people with insomnia.

- Breathing problems may occur with overuse or in people with pre-existing respiratory illness.

- Long-acting drugs have a very high rate of residual daytime drowsiness compared to others. They have been associated with a significantly increased risk for automobile accidents and falls in the elderly, particularly in the first week after taking them. Shorter-acting benzodiazepines do not appear to pose as high a risk.

- There are reports of memory loss (so-called traveler's amnesia), sleepwalking, and odd mood states after taking triazolam (Halcion) and other short-acting benzodiazepines. These effects are rare and probably enhanced by alcohol.

- Because benzodiazepines cross the placenta and enter breast milk, pregnant and nursing women should not use them. There are some reports of an association between the use of benzodiazepines in the first trimester of pregnancy and the development of cleft lip in newborns. Studies are conflicting at this point, but other side effects are known to occur in babies exposed to these drugs in the uterus.

- In rare cases, overdoses have been fatal.

Interactions. Benzodiazepines are potentially dangerous when used in combination with alcohol. Some drugs, such as the ulcer medication cimetidine, can slow the breakdown of benzodiazepine.

Withdrawal Symptoms. Withdrawal symptoms usually occur after prolonged use and indicate dependence. They can last 1 - 3 weeks after stopping the drug and may include:

- Gastrointestinal distress

- Sweating

- Disturbed heart rhythm

- In severe cases, patients might hallucinate or experience seizures, even a week or more after they stop taking the drug.

Rebound Insomnia. Rebound insomnia, which often occurs after withdrawal, typically includes 1 - 2 nights of sleep disturbance, daytime sleepiness, and anxiety. The chances of rebound are higher with the short-acting benzodiazepines than with the longer-acting ones.

Narcotic Pain Relievers

Narcotics are pain-relieving drugs that act on the central nervous system. They are sometimes prescribed for severe cases of restless legs syndrome (RLS). They may be a good choice if pain is a prominent feature. Some evidence also suggests that narcotics reduce the frequency of periodic leg movements.

There are two types of narcotics, both of which have been used for severe RLS:

- Opiates (such as morphine and codeine) come from natural opium. Some patients report relief with the use of the opiate fentanyl (Duragesic), available in skin patch form. An implanted pump that uses morphine and an anesthetic called bupivacaine is showing promise for patients with severe RLS. The pump delivers the drugs to the fluid surrounding the spinal cord (cerebrospinal fluid).

- Opioids are synthetic drugs. The most common example is oxycodone (Percodan, Percocet, Roxicodone, OxyContin, Methadone, Hydrocodone).

Although the use of narcotics for severe RLS is controversial, some studies have suggested that even when the treatments are long-term, they are rarely addictive for pain sufferers except among patients with a history of substance abuse.

The use of such drugs may be beneficial when included as part of a comprehensive pain management program. Such a program involves screening prospective patients for possible drug abuse, and regularly monitoring those who are taking narcotics. Doses should be adjusted as necessary to achieve an acceptable balance between pain relief and side effects. Patients on long-term opiate therapy should also be monitored periodically for sleep apnea, a condition that causes breathing to stop for short periods many times during the night. Sleep apnea may worsen symptoms of RLS, insomnia, and other complaints.

Tramadol. Tramadol (Ultram) is a pain reliever that has been used as an alternative to opioids. It has opioid-like properties, but is not as addictive. (However, there are reports of dependence and abuse with this drug as well.) Withdrawal after long-term use (longer than a year) can cause intense symptoms, including diarrhea, insomnia, and even restless legs syndrome itself.

Antiseizure Drugs

Antiseizure drugs -- such as gabapentin (Neurontin), valproic acid (valproate, divalproex, Depakote, Depakene), and carbamazepine (Tegretol) are being tested for restless legs syndrome (RLS). On April 6, 2011, the FDA approved gabapentin enacarbil, a new form of gabapentin, for the once daily treatment of moderate to severe RLS. Gabapentin enacarbil converts to gabapentin in the intestines, and therefore may reduce some of the side effects experienced by patients taking antiseizure medications. (Common side effects included mild sleepiness and dizziness.) The newly approved drug is marketed under the name Horizant Extended Release.

Side Effects. All antiseizure drugs have potentially severe side effects. Therefore, patients should try these medications only after non-drug methods have failed. Side effects of many anti-seizure drugs include nausea, vomiting, heartburn, increased appetite with weight gain, hand tremors, irritability, and temporary hair thinning and hair loss (taking zinc and selenium supplements may help reduce this last effect). Some antiseizure drugs can also cause birth defects and, in rare cases, liver toxicity. Gabapentin may have fewer of these side effects than valproic acid or carbamazepine.

Other Drugs

Antidepressants. Bupropion (Wellbutrin), a newer antidepressant, may be helpful for restless legs syndrome (RLS). Bupropion is a weak dopamine reuptake inhibitor -- it causes a slight increase in the availability of dopamine in the brain. The drug is not addictive and does not have the severe side effects of other RLS drugs, but more research is needed to determine if it is useful.

Clonidine. Clonidine (Catapres), a drug used for high blood pressure, is helpful for some patients and may be an appropriate choice for patients who have RLS accompanied by hypertension. It also may help patients with RLS who are undergoing hemodialysis.

Baclofen. The anti-spasm drug baclofen (Lioresal) appears to reduce intensity of RLS (although not frequency of movements).

Alpha-2 Delta Blockers. Gabapentin and gabapentin enacarbil appear to help RLS sufferers. Pregabalin is currently under study.

Resources

- www.aasmnet.org -- American Academy of Sleep Medicine

- www.sleepfoundation.org -- National Sleep Foundation

- www.ninds.nih.gov -- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/ncsdr/ -- National Center on Sleep Disorders Research

- www.rls.org -- Restless Legs Syndrome Foundation

- www.wemove.org -- Worldwide Education and Awareness for Movement Disorders

References

Bayard M, Avonda T, Wadzinski, J. Restless Legs Syndrome. American Family Physician. 2008;78(2):235-240.

Gringas P. When to use drugs to help sleep. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93(11):976-81.

Hening WA. Current Guidelines and Standards of Practice for Restless Legs Syndrome. AmJ Med. 2007;120(1A):S22-S27.

Hornyak M, Rupp A, Riemann D, et al. Low-dose hydrocortisone in the evening modulates symptom severity in restless leg syndrome. Neurology. 2008;70(18):1620-2.

Kushida CA. Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Quality of Life Issues in Restless Legs Syndrome. AmJ Med. 2007;120(1A):S4-S12.

Kushida CA, Becker PM, Ellenbogen AL, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of XP13512/GSK1838262 in patients with RLS. Neurology. 2009;72(5):439-46.

Lettieri CJ, Eliasson AH. Pneumatic compression devices are an effective therapy for restless legs syndrome: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, sham- controlled trial. Chest. 2009;135(1):74-80.

Lohmann-Hedrich K, Neumann A, Kleensang A, et al. Evidence for linkage of restless legs syndrome to chromosome 9p: are there two distinct loci? Neurology. 2008;70(9):686-694.

Ondo WG. Restless Leg Syndrome. Neurol Clin. 2009;27(3):779-799.

Ong KH, Tan HL, Tam LP, et al. Accuracy of serum transferrin receptor levels in the diagnosis of iron deficiency among hospital patients in a population with a high prevalence of thalassaemia trait. Int J Lab Hematol. 2008;30(6):487-493

Picchietti D. Restless legs syndrome: prevalence and impact in children and adolescents--the Peds REST study. Pediatrics. 2007; 120(2): 253-66.

Restless Leg Syndrome Foundation. RLS Name Change: Willis-Ekbom Disease. Available online. Last accessed: October 1, 2011.

Stefansson H, Rye DB, Hicks A, et al. A Genetic Risk Factor for Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:639-47.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Horizant to treat restless legs syndrome. FDA News Release, April 7, 2011. Available online. Last accessed September 17, 2011.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA's MedWatch Safety Alerts: July 2010. Available online. Last Accessed 21 September, 2010.

|

Review Date:

11/6/2011 Reviewed By: Reviewed by: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |